HELENA DE KAY GILDER

Although she began her career as a painter, Helena de Kay Gilder (1846-1916) increasingly dedicated her considerable energy and talent to advocating for art, artists, and women, according to her own vision. She is remembered as a founder of the Art Students League and the Society of American Artists and for her vibrant creative partnership with her husband, Richard Watson Gilder, poet and editor of Scribner’s and Century magazines.

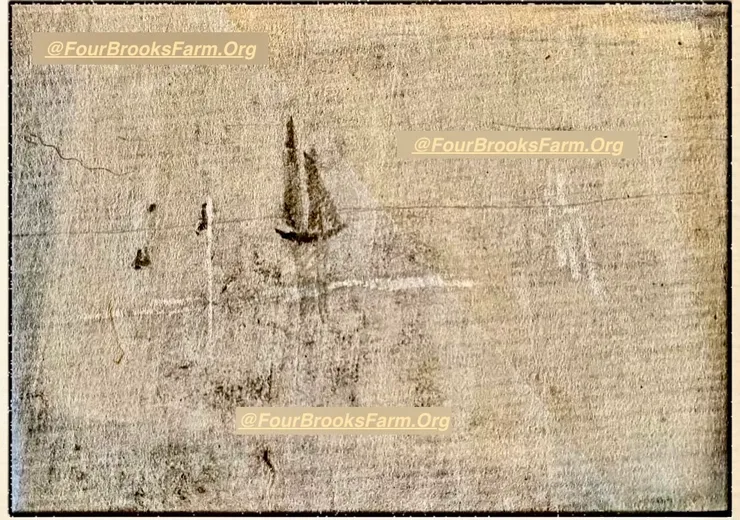

According to local historians, the Gilders “forever changed” Marion, Massachusetts when they began summering there in 1881. Their presence in the then small, out-of the-way coastal village ushered in a “Golden Age,” as “authors, artists, musicians, all the great of the artistic Bohemian America followed the Gilders to Marion.” Helena and Richard bought a ramshackle old house in the village and an old stone building in the woods behind it, dubbing the house “Gilder Lodge,” and the building “The Old Stone Studio.” The building, which still stands on Spring Street in Marion, served as a place for Helena to paint and for Richard to read manuscripts. It became a gathering place for their many friends, and they held amateur theatricals there, as well as amusements for children. One summer, Helena shared The Old Stone Studio with August Saint-Gaudens, by then the leading sculptor in America. First Lady Frances Folsom Cleveland posed for him there when he was commissioned to create a bronze medallion portrait of her. Henry James was a frequent visitor and set part of his novel, The Bostonians, in a town called “Marmion,” modeled after Marion. In 1893, the Gilders changed their summer residence to Tyringham, Massachusetts in the Berkshires, buying Four Brooks Farm there in 1899.

Born in New Jersey in 1846 to naval officer George Colman de Kay and Janet Drake de Kay, Helena was the sixth of seven children. After Helena’s father died when she was two years old, her mother moved the family to Dresden, Germany, a renowned center of art, architecture, and culture, nicknamed “Florence on the Elbe.” There Helena learned French, German, and Italian and developed a passion for art. In 1861, Helena’s mother moved the family again, this time to Newport, Rhode Island to be near Helena’s sister, Katharine, who had just given birth to her first child. Helena was enrolled in a boarding school in Connecticut and spent her school vacations and summers in Newport. The de Kay family was friendly with the family of Henry James there, and Helena and Henry became lifelong friends. In Newport Helena also met stained glass artist and painter John LaFarge, who became her teacher and mentor.

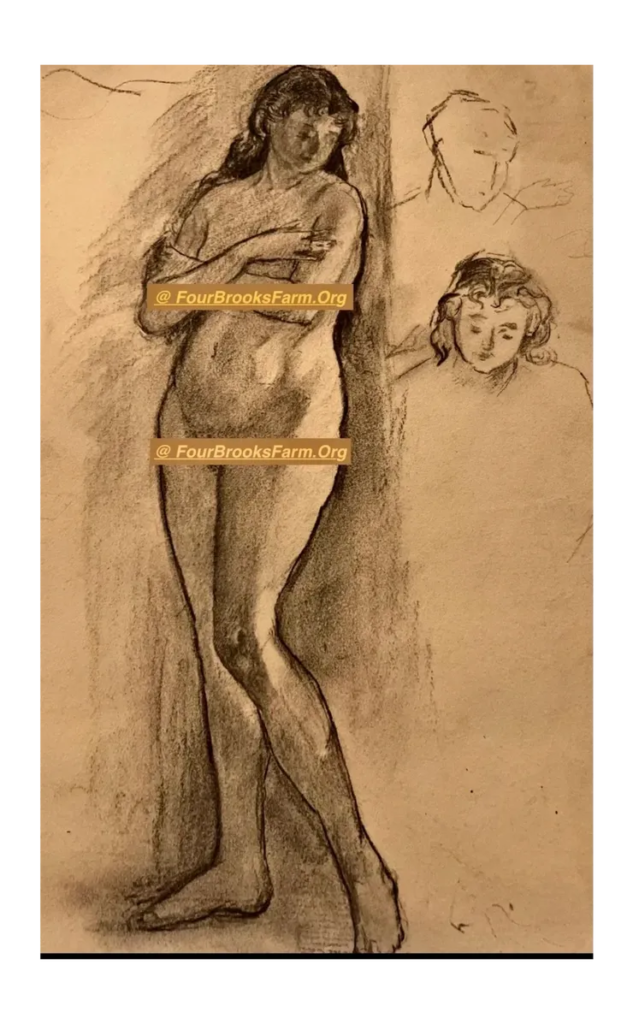

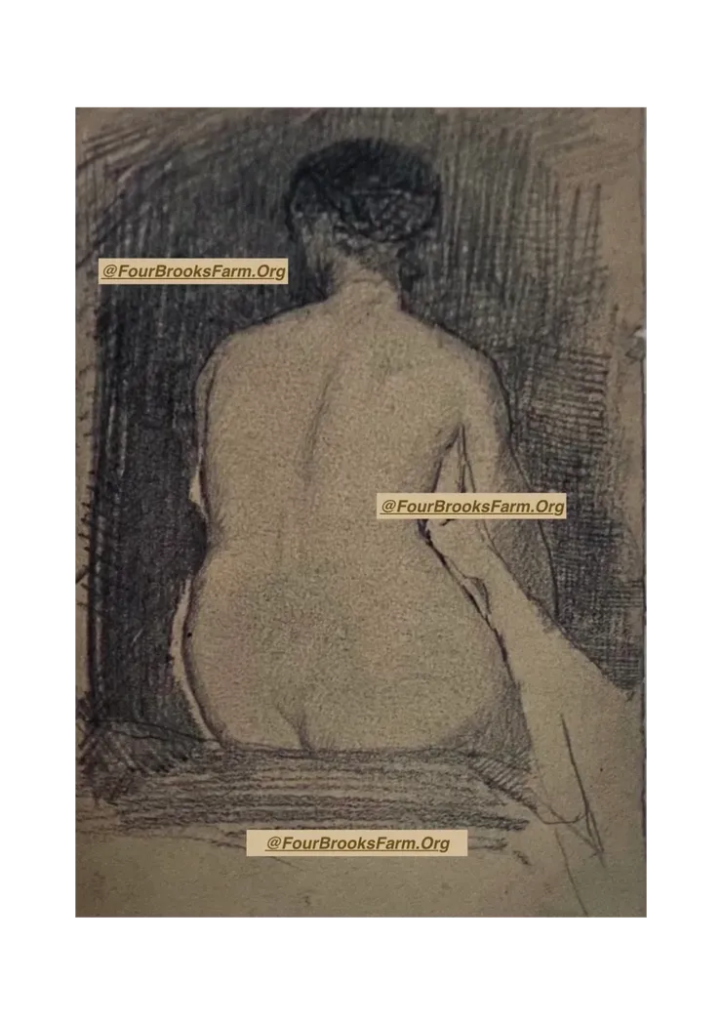

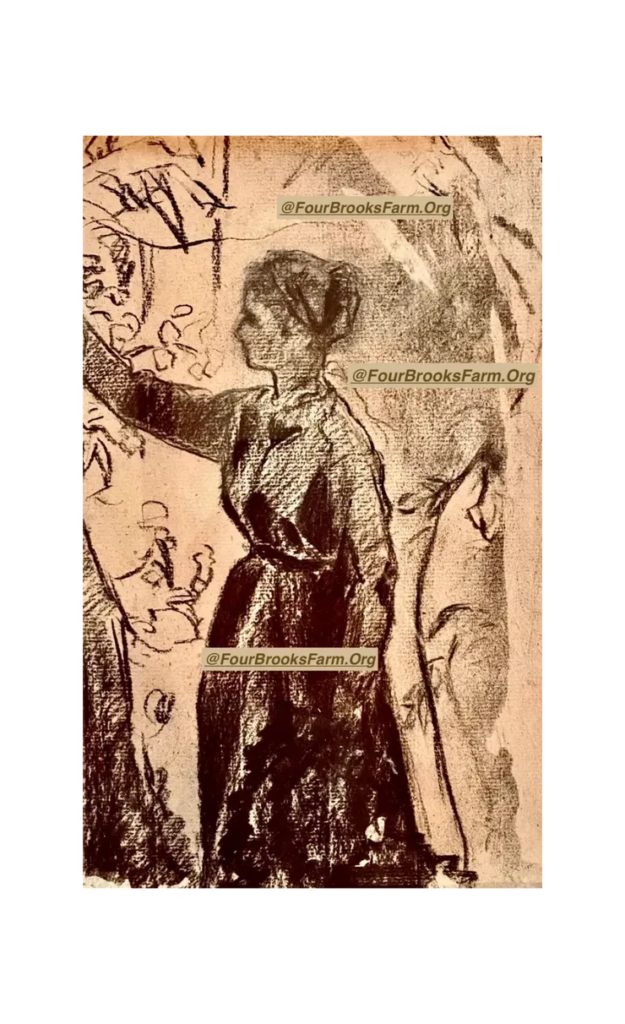

Helena continued her art studies by attending the Free School of Art for Women at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City from 1866-1869. She made an intimate friendship with fellow Cooper Union student Mary (Molly) Hallock, who later became a famous illustrator and novelist, chronicling her life in Idaho, Colorado, and California after moving west with her husband, Arthur Foote. Helena and Molly remained close friends throughout their lives, corresponding through letters over 50 years. Helena also attended classes at the Ladies Art Association and the Antique School of the National Academy of Design (NAD), developing expertise in figure and still-life painting. Helena and fellow student Maria Oakey shared a studio in New York and associated with the intellectuals and artists of the day, including LaFarge and Henry James. Maria and Helena attended the first life drawing class open to women at the NAD in 1871 (it had been previously considered unthinkable for female artists to draw male nudes). During this time, Helena also met painter Winslow Homer through her brother, art critic Charles de Kay. Homer’s letters suggest that he fell in love with Helena and proposed marriage, which she refused.

In 1872, Helena was introduced by novelist Helen Hunt Jackson to Richard Watson Gilder, then managing editor for Scribner’s Monthly magazine, at the magazine’s offices. Their daughter, Rosamond Gilder describes their courtship in her edition of her father’s letters: “With her family traditions, her familiarity with European literature, her knowledge and appreciation both of art and music, she opened new fields of interest and enjoyment to her eager ‘comrade.’ Together they went to concerts and art exhibitions, they listened to lectures, read poetry, and studied Dante, with an ever-increasing pleasure and intimacy.” Helena and Richard were married in 1874 and moved into an old carriage house near Union Square that had been remodeled under the direction of their friend, prominent architect Stanford White.

Helena and Richard named the carriage house “The Studio,” and it became a salon for “artists, and actors, musicians and writers, who mingled with a varied collection of philanthropists, millionaires, and penniless philosophers,” according to the biographer of poet Emma Lazarus, one of Helena’s close friends. The Gilders’ “Friday Nights” at The Studio were legendary, reminisced another friend, Will Low: “To the hospitable welcome of that modest dwelling everyone who came to New York in those days, bearing a passport of intellectual worth, appeared to find his way.”

In 1875, frustrated with the conservative instruction policies and inconsistent teaching schedule at the National Academy of Design, Helena joined with other dissatisfied students to form the Art Students League. The League, dedicated to progressive art instruction, was founded on the European atelier model in which autonomous studios are directed by the creative authority of individual instructors. Equality between women and men, as students and as teachers, was mandated, and life drawing was available every weekday. The Art Students League flourished and still exists today, true to the ideals of its founders, with a long and diverse list of famous artists who studied there, including Georgia O’Keeffe, Alexander Calder, Norman Rockwell, Thomas Hart Benton, Jackson Pollock, Louise Nevelson, Isabel Bishop, Mark Rothko, and Louise Bourgeois.

In 1877, Helena again joined fellow artists to address frustration with the National Academy of Design. This time the issue was the NAD’s conservative and limiting exhibition policies. The work of younger, more avant-garde artists was routinely rejected by the NAD for exhibitions. To provide a forum for new and diverse trends in art and to encourage women artists, Helena, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and painters Wyatt Eaton and Walter Shirlaw gathered at the Gilders’ home and formed the Society of American Artists. The Society held its first exhibition in 1878 including works by Helena, Saint-Gaudens, John LaFarge, J. Alden Weir, and Albert Pinkham Ryder (from New Bedford, Massachusetts). By 1890, the Society had 100 exhibiting artists. However, over the following decade, the new trends in art the Society had championed had become more mainstream, and the society lost members and eventually merged with the NAD.

Helena gave birth to her first of seven children, Marion, in 1875, and to her second child, Rodman in 1877. Sadly, Marion died at age 3 in 1878, and Helena and Richard lost another child, Richard, Jr., as an infant in 1880. Their daughter Dorothea was born in 1882, son George in 1885, daughter Francesca in 1888, and daughter Rosamond in 1891. Helena continued painting professionally until 1886, when she resigned her membership in the Society of American Artists and shifted her primary focus to nurturing her family. However, her involvement in the arts continued with her support of other artists. Over the course of their 35-year marriage, Helena and Richard befriended and mentored scores of artists, writers, and others, continuing to host salons in New York and at their summer homes in Massachusetts. They tirelessly advocated for their friends’ work, and used the publishing power of Scribner’s, which became Centurymagazine under Richard’s editorship, the most prestigious periodical of the day. Helena and Richard were on the forefront of American cultural life in their time, respected and admired arbiters of the arts, with considerable social and political influence, as well. President Grover Cleveland and his wife Frances were close friends and frequent guests of the Gilders, as were Henry James, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, Stanford White, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Edith Wharton, actors Joe Jefferson and Helena Modjeska, painter Cecilia Beaux, art critic Marianna Griswold Van Rensselaer, and President Theodore Roosevelt, to name a few.

In the 1890s, as the women’s suffrage movement gathered energy, Helena’s vision of advocating for women’s rights took the form of her adamant opposition to a political role for women. In today’s culture, this position would seem an about-face, but for Helena, in her milieu, it was consistent with her choices and point of view. According to historian Susan Goodier, Helena joined a group of women who wanted to “retain their feminine identities as protectors of their homes and families, a role they felt was threatened by the imposition of masculine political responsibilities.” In 1894, Helena wrote a letter to her friend Molly Hallock Foote, detailing her reasons for opposing women’s suffrage. Before she could mail it, Richard took the letter to the offices of The Critic, a literary magazine edited by his sister and brother. In spite of the letter’s content being unusual for their magazine, they published it as a lead article. The letter was well received by many and was printed and distributed as a pamphlet. Helena was widely praised as “a voice for the anti-s,” served on the executive board of the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, and appeared before the New York State Senate judiciary committee to assure legislators that women did not want to vote.

Helena and Richard continued to widen their circle and actively support artists and writers, travelled in the U.S. and Europe, and watched their children grow. In 1909, Richard died of a heart attack, and their long partnership came to an end. Helena, at age 63, was bereft. She withdrew from the anti-suffrage movement and many of her other public activities. As a friend explained, “With her husband’s death, her own personal life died, too. What was left was her children’s, and outside interests, excepting always through books & friendly talks, faded into unimportance, & dropped away.” Helena died at age 70 in 1916 and was buried near her husband in his hometown of Bordentown, New Jersey. Helena perhaps is best remembered as her friend Cecilia Beaux described her: “Although she had the softest and most caline of smiles to bestow . . . Her spirit was as old, as experienced, as wise, and as enigmatic as an innumerable series of lives could make it. It was also as tolerant of the weaknesses of humanity, and even its stupidities. She accepted but rarely explained why. The warm tones of her marvelous voice had a vibration brought from depths of what she knew, what she suffered, and what she could give of support. One could follow her counsel unafraid.”

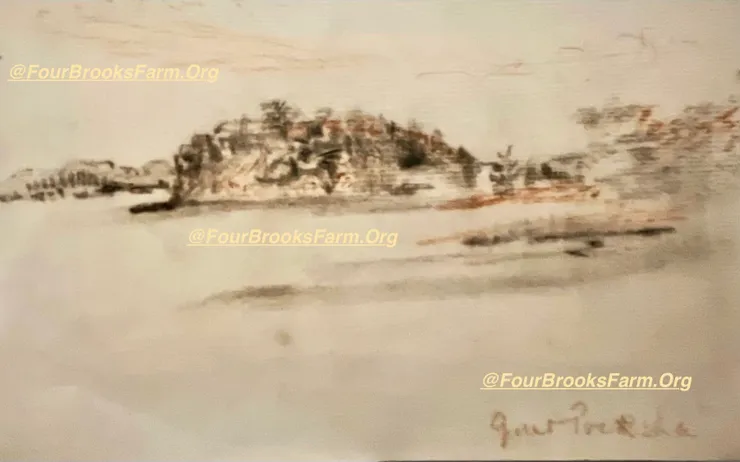

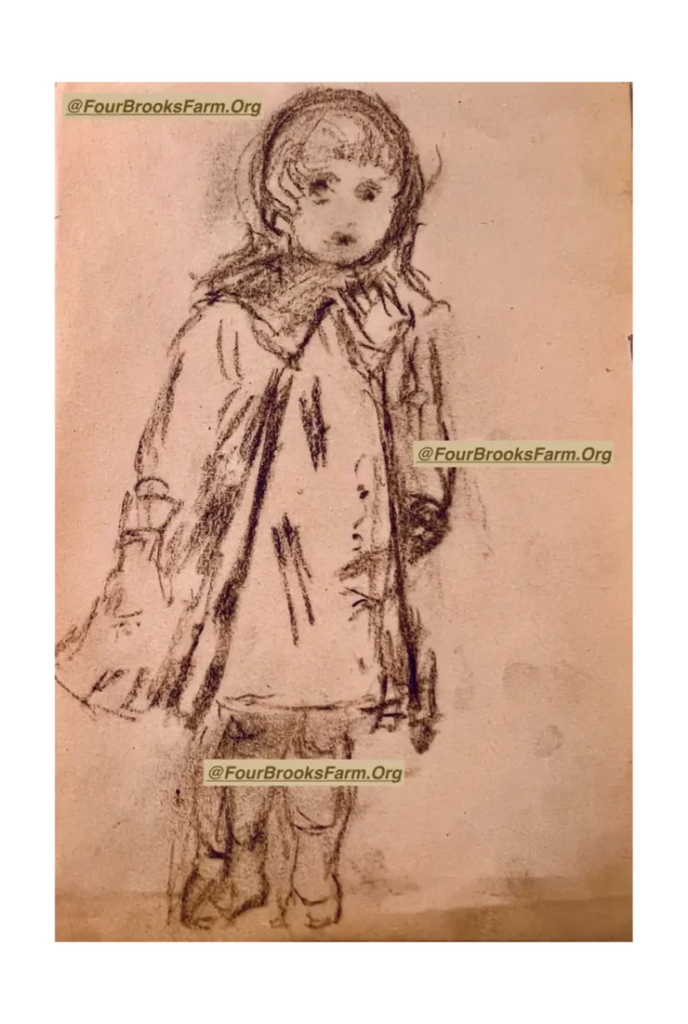

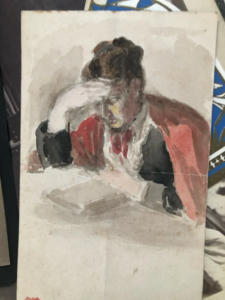

Artwork by; Helena Dekay Gilder Era; 1846-1916